|

|

|

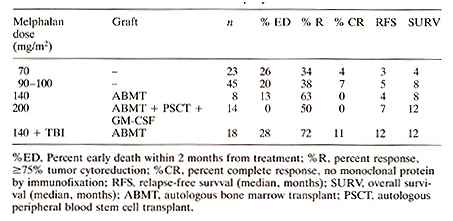

Introduction Multiple myeloma remains an incurable systemic malignancy with a median survival not exceeding 3 years [1] .Modifications of standard therapy with melphalan and prednisone have not improved patients' prognosis [2]. As a result, dose intensification studies have been undertaken to determine whether such approach would be associated with enhanced tumor cell kill with increased response rates as well as extended remissions and survival [3-11]. Results Melphalan Dose-Response Relationship Evaluation of increasing doses of intravenously applied melphalan resulted in increased response rates (>=75% tumor cytoreduction) as well as extension of relapse-free and overall survival durations (Table 1). Beyond 140 mg/mę¸ melphalan, autologous hemopoietic stem cells were required, which also Table 1. Melphalan dose escalation in

refractory myeloma

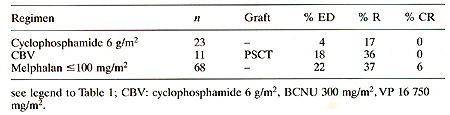

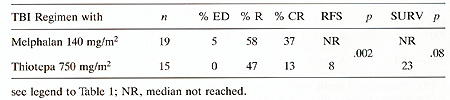

When comparing maximally tolerated doses (MTD) of cyclophosphamide and melphalan without autografts and also hemopoietic stem cell supported cyclophosphamide with added BCNU and etoposide (CBV), melphalan at subtransplant doses appeared more effective than cyclophosphamide at MTD and comparable in efficacy to the CBV regimen with blood stem cell support (Table 2) .The virtual lack of extramedullary toxicity with melphalan up to 100 mg/m² justified further dose escalation and addition of total body irradiation ( see above) . In VAD-responsive myeloma we had the opportunity of comparing TBI regimens that included either melphalan or thiotepa. Relapse-free and overall survival durations were superior when melphalan rather than thiotepa was employed (Table 3). These results support the notion that melphalan is one of the most active cytotoxic agents for the therapy of myelomatosis. Table 2. Efficacy of different

alkylating agents in refractory myeloma  Table 3. Melphalan or thiotepa with TBI in responsive myeloma

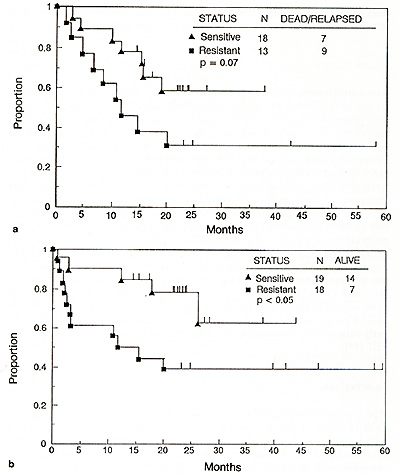

Among 55 patients receivingTBI-containing regimens with either melphalan or thiotepa, the worst outcome was noted among patients with VAD-resistant relapse [9]. When considering the major difference in activity between melphalan and thiotepa ( see above) , further analysis was performed on the subset of patients receiving melphalan and TBI. Those treated while still responsive to standard doses of therapy had superior relapse-free and overall survival times compared to patients with resistant myeloma (Fig. 1).

Based on relatively comparable results obtained with melphalan at 200 mg/m² [8] and melphalan at 140 mg/m² with added TBI at 850 cGy among patients with responsive myeloma [9], the double transplant program was developed employing two cycles of melphalan at 200 mg/m² 3-6 months apart using hemopoietic stem cells collected prior to the first intensive therapy [121. Preliminary data indicate that this approach is feasible in principle without early mortality among almost 50 patients who have completed one cycle of treatment. Few relapses were seen between 3 and 6 months after the first transplant. Approximately 20 patients have received a second transplantation, and hematologic reconstitution was not significantly delayed provided that quantity and quality of hemopoietic stem cells were adequate. There was no evidence of cumulative extramedullary toxicity. Compared with the preceding TBI-containing regimens, extramedullary toxicity, especially stomatitis,was reduced and early mortality decreased. This was perhaps in part related to the concurrent use of autologous blood stem cells and GM-CSF [13]. The follow-up time is still too short to permit comparisons of the double transplant approach with the preceding melphalan-TBI program. As a result of eliminating treatment-associated mortality, early survival data are superior with the recent program that does not utilize TBI [14].

Autologous hemopoietic stem cells permit administration of marrowablative doses of therapy even to elderly patients with multiple myeloma without excessive toxicity. Higher frequencies of complete remission have been obtained even in advanced and refractory disease which had not been obtained with standard doses of treatment applied to newly diagnosed patients. Melphalan appears to be the single most active agent among a variety of drugs tested and suitable for repeated application without undue toxicity. Compared with historical data, autotransplant-supported intensive therapy seems to extend survival in refractory myeloma by at least one year and, using cautious estimates, by 3 years when applied for response consolidation. The availability of hemopoietic growth factors such as GM-CSF permits speedy collection of blood stem cells following high dose cyclophosphamide priming, and their joint use with autologous hone marrow and GM-CSF also post-transplantation has shortened the duration of bone marrow aplasia to a few days and hence reduced the risk of fatal infection during agranulocytosis markedly.

Supported in part by CA37161-01 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

1. Barlogie B, Epstein ], Selvanayagam P, Alexanian R (1989) Review

article: plasma cell myeloma -new biological insights and advances

in therapy. Blood 73:865-879 |